Chapter 1 Poverty and measurement theory principles

Abstract

This chapter introduces the concept of poverty and draws upon measurement theory to frame some of the potential solutions -from the statisical point of view- to some of the challenges in the production and empirical assessment of poverty indices. The roles of poverty definitions, researcher’s value judgements, desirable properties of poverty indices, survey data and measurement error in the production of poverty measures are described.

1.1 The Concept of Poverty

Poverty is one of the capital concepts in social sciences. Economics, sociology, psychology, politics and so forth, work with constructs. In the realm of the social sciences, concepts are not attribute or feature directly observable using univariate data. Poverty shares this very feature in that it is a construction of the human mind to depict a state of low living standards. Yet, poverty is something that can be grasped intuitively by anyone and, at the same time, a construct with several contested interpretations. We thus have judgements and prejudices about poverty and we aim to measuring not by direct observation but by indirect approximations based on systems of data.

Poverty has several meanings and part of the difficulty in measuring it has to do with the existence of different definitions. Spicker, Alvarez, & Gordon (2006) suggest that the definitions proposed in the literature can be clustered into three main groups: material (needs, resources and deprivation), economic (living standards, inequality and economic position) and social conditions (entitlements, social security, exclusion, dependence and social class). Spicker et al. (2006), nonetheless, underline the importance of working with scientific definitions of poverty as they meet the standards of the philosophy of science: definitions that are testable so that are falsifiable in a clear way. The contemporary literature defines poverty in terms of both low living standards and resources (Gordon (2018); Gordon (2006)). This broad definition suggests the existence of two sub-population groups that are meaningful and falsifiable in the sense that their profile should predict outcomes that in theory are caused by poverty- mortality, poor health, economic stress, etc.

Townsend (1979), in agreement with the standards of philosophy of science, argued that poverty should and can be treated scientifically in that it can be objectively defined and measured. He put forward a theory of poverty and relative deprivation where he stated that the concept of deprivation was central for the definition of poverty in that it connects command of resources with low living standards (Townsend, 1987). The link between lacking something and a notion of resources to access things leads to a simple scientific definition of poverty (Gordon, 2006):

Poverty can be defined as the lack of resources overtime where material and social deprivations are its consequences.

This definition, of course, opens up several questions because it does not clarify what is the set of deprivation that matters and in what sense lacking something is a standard to classify people as poor or not poor. Furthermore, it is not the only definition of poverty and there are other definitions that use different concepts -commodities, resources, capabilities- and seem very differently constructed (see below). Nonetheless, there are many discrepancies that are a matter of semantics (Gordon, 2006) and this definition is useful because it is simple and it can be debated more transparently and permits to see the similarities and dissimilarities between this definition and other well-known concepts in the literature: deprivation, resources, living standards, capabilities, consumption, and so forth.

At the core of several conceptual debates lies the question about the best domain to define deprivation, i.e. what set of necessities one needs to take into consideration. One of the most well-known disputes is the discussion in the 1980s about absolute and relative poverty. Townsend (1987) argued that poverty is relative in the sense that it varies across time and space- the identification of the relevant domain depends on what a society regards as the minimum according to the prevailing living standards. Sen (1983) was the most notable thinker against to the idea of poverty as a relative concept. He suggested that poverty was absolute in the sense of not having certain basic opportunities- failure in capabilities. Altimir (1979) concluded that Sen and Townsend were talking about two nested thresholds. The absolute core which is universal and a relative one which varies across societies and time.

In a series of exchanges in Oxford Economic Papers in the 1980s, Townsend and Sen discussed their views on poverty as an absolute or relative concept. As (Gordon, 2006) points out most of the disagreement is a matter of semantics. Boltvinik (1998) provides an recapitulation of the exchanges and he notes that part of the disagreement has to do with the lack of clarity on the space to identify poverty: commodities, resources, capabilities and deprivation. Sen (1983) acknowledged that commodities and characteristics change overtime but to identify poverty researchers must establish when people fail to achieve certain minimum capabilities. There are however, two difficulties in operationalising capabilities. First, Thorbecke (2007) points out that measuring capabilities implies observing them ex ante but in practice only outcomes -achieved functionings- can be measured. Second, the is the challenge of specifying the minimum capability set. Whereas some authors have proposed a minimum list (Nussbaum, 2000); others like Sen (2005) and Alkire (2007) have been against this idea. At the core of this debate seems to be a lack of clear distinction between a theoretical list (which can be authoritative if imposed without any sort of evidence) and a backed-up list by some sort of validation via public reasoning or empirical exercises.

Measurement of achieved functionings provides the basis to resolve the dispute about absolute-relative definitions of poverty (Spicker et al., 2006). As it implies that capabilities are operationalised through socially defined commodities and characteristics (the next section discusses how this fits a measurement framework that draws on latent variables).1 In the space of outcomes (\(X\)), there is very little practical difference between the concepts of achievements and deprivation \(x\). However, the question about what are the contents (\(X\)) of the definition of poverty remains unanswered at this point. The solution lies in establishing the space of functionings (that relate to deprivation capability in Sen’s terms) or the space of deprivation according to the standards of society in Townsend’s framework. Both authors acknowledged that such space is multidimensional in the sense that it relates to the minimum diverse aspects than enable humans to function/participate in society.

1.2 Theoretical dimensions of poverty

Theories of human need, capabilities and relative deprivation have been put forward to frame the (\(j\)) dimensions and its contents (\(x_{ij}\)) that should be included in both the definition and measure of poverty. Most notably, the Unsatisfied Basic Needs approach, with a long track record in Latin America, draws on theories of human need such as those proposed by Maslow (1943) and Max-Neef, Elizalde, & Hopenhayn (1992). Altimir (1979) and Boltvinik & Hernández-Láos (2001) draw upon the concept of human needs (instead of capability or relative deprivation) to define poverty in terms of unmet basic needs. The UBN approach has had at its core the housing dimension (access to water and sanitation and materials of the dwelling) plus education, food and health deprivation. Boltvinik (2014) reviews the different variants of the UBN and it is possible to appreciate the different dimensions of poverty (as well as diverse aggregation methods and strategies to identify the poor) where he identifies as the improved variant the one that includes time and underpins the Integrated Poverty Measurement Method (IPMM) (Boltvinik, 1992, p. Boltvinik2001). A recently popular variant of the UBN are the hybrid approaches that combine UBN and social rights. Notably, UNICEF’s first international measure of child poverty proposes eight dimensions (Gordon, Nandy, Pantazis, Pemberton, & Townsend, 2003). A similar hybrid variant of the UBN is the Mexican Multidimensional Measure. It has two domains: income and social rights. The human rights domain has five dimensions: Housing, social security and health, education, essential services and food deprivation (Cortés, 2014, p. CONEVAL2011d). The capability-based dimensional models are very similar to the UBN approaches. For example, drawing upon the capability approach, Klasen (2000) proposes a core deprivation index that it is fairly similar to the standard UBN dimensions. This is understandable as it focuses on outcomes that often relate to basic human needs. These models are fairly recent, and its dimensional structure heavily draw upon the original UBN variants implemented in the 1970s and 1980s in Latin America (Boltvinik, 2014) (Chapter XX discusses some of the aggregation novelties introduced by this approach). The most popular implementation is the UNDP-OPHI international model for acute poverty which classifies the indicators into 3 dimensions: standard of living, education and health (UNDP, 2014). As in the UBN measures the housing facilities and conditions are central for the measure. The implementations in Latin America have put forward a five-dimensional structure: housing, basic services, living standard, education and employment (Santos & Villatoro, 2016).

Relative deprivation has also a hierarchical structure, but it proposes different dimensions and subdimensions. Townsend (1979)’s original model suggested two main domains: material and social deprivation but with four and seven subdimensions, respectively. For material: dietary, clothing, fuel and light, household facilities and amenities, working conditions, health and educational. For social: Environmental, Family, Recreational and Social (Townsend, 1979, pp. 1173–1174). There have been several models that draw upon relative deprivation but the theory behind them is not as explicit as in the case of the UBN or the Townsend model (Betti, Gagliardi, Lemmi, & Verma, 2015; A.-C. Guio, 2009; Whelan, Nolan, & Maitre, 2006). These nonetheless suggest rather different dimensional structure. A.-C. Guio (2009) proposes a three dimensional model comprising economic strain, enforced lack of durables and housing-related deprivation; Whelan et al. (2006) propose five dimensions (economic strain, consumption, housing facilities, neighbourhood environment, health status) and Betti et al. (2015) put forward seven dimensions that are contain most of Whelan et al. (2006)’s proposal (Chapter X discusses more in detail the implications of these models).

Drawing upon this review of the conceptualization of poverty, throughout the book we will be referring to Townsend (1979) definition (Gordon, 2006):

Poverty is the lack of command of resources overtime and deprivations its consequence.

This concept of poverty is useful because it is simple and is not in tension with many of the conceptual debates described above. The definition acknowledges that deprivation is multidimensional in that it refers to the unmet needs/functionings that are regarded as essential by society in a given point in time. But, the definition is also useful because it clearly links a cause (poverty) with a consequence (observed deprivation). This is key as from the perspective of philosophy of science permits connecting a construct (human invention) with a statistical framework that works with multivariate data and indirect approximations to a phenomenon.

There is another aspect that is very useful in Townsend (1979)’s definition. One of the difficulties in poverty measurement is that many measures confound outcomes with predictors of poverty, so that sometimes predictors like unemployment or disability are included with deprivation. This, of course, adds error because we are not interested in estimating poverty but in measuring it. If we would have data on deprivation we would, of course, only have one option- fitting a predictive model, like in the case of small-area estimation (Rao & Molina (2015)). In Townsend’s theory low command of the following five resources is the main cause of multiple forms of deprivation (Townsend, 1979, p. 55):

1. Cash income a) Earned b) Unearned c) Social security

2. Capital assets a) House occupied by family b) Assets and savings

3. Value of employment and benefits in kind a) Employers’ fringe benefits, subsidies and value of occupational insurance b) Occupation facilities

4. Value of public social services in kind a) Goverment subsidies and services, e.g. health, education and housing but excluding social security

5. Private income in kind a) Home production b) Gifts c) Value of personal supporting services

This is a UK-centred definition of resources and not all these resources might matter in all countries. For example, Boltvinik & Hernández-Láos (2001) proposes time as a resource and in most UBN-based measures services are included as a dimension of poverty. This, for instance, is not in contention with Townsend’s definition, in fact, the UBN measures look at deprivation (effective access) of services -low command of this type of resource- results in deprivation.

It is also important to note, the similarities between Townsend’s definition and the Canberra-Group (2012) definition of income. The overlap is high. This sometimes confuses people as they think that Townsend (1979) proposed that poverty is the low command of income overtime. This is incorrect, the problem is that in most surveys our best proxy of resources is income often measured using the Canberra-Group (2012) convention. This the reason why the Poverty and Social Exclusion (PSE) or other approaches that combine resources of deprivation -like CONEVAL in Mexico- actually intersect income and deprivation.

So far we have discussed some of the elements needed to define and measure poverty, but we have discussed very little what happens once the substantive aspects of poverty have been established. This begs the following question: How the poor are correctly identified using available data? This is the question of this book: What criteria and principles lead to falsify the contents and identification of a poverty scale? To better frame the question is appropriate to review the challenges involved in poverty measurement.

1.3 The measurement of poverty and its challenges

The concept of poverty involves raising a series of assumptions about the existence of a minimum living standard that permits meaningfully to split a population into two groups. Researchers therefore have to make several decisions with regard how to select the dimensions and its indicators but also about how what is the best way to aggregate the information so that the poor is accurately identified (Alkire, 2007; Thorbecke, 2007). These result into a series of decisions that demand theoretical and empirical justification:

- Specifying the \(j\) dimensions

- Specifying the contents (indicators) of each dimension \(x_{ij}\)

- Deciding the cut off \(x_{ij}<z\) of the indicators

- item Establishing a measurement model about the relationship between dimensions and indicators

- item Deciding the relative contribution (weights) \(w_{j}\) of some indicators/dimensions

- item Deciding how to aggregate the information to rank the population

- item Deciding how to split such ranking into two meaningful groups \(p_k (x_i;z) = 1\) if \(c_i\leq k\) and \(p_k (x_i;z) = 0\) otherwise

1.3.1 Challenges in selection of dimensions, contents, cut offs and weights

With regard the first three, Gordon & Nandy (2012) point out that although there is a consensus that poverty is multidimensional, there is little consensus about the number, contents and nature of the dimensions of poverty. Theoretical frameworks rarely go that far and, although there is some overlap of the dimensions used in different perspectives, there is very little agreement about the content and the nature of the interactions between and within dimensions. Alkire (2007) provides and overview of the different approaches that a researcher can employ to decide the dimensions, indicators and its interaction (public consensus, existing data, convention, deliberative participatory process, data on people’s values). The typical dimensions proposed from the capability, UBN and relative deprivation were overviewed in the previous section. One critical example, in that is grounded on theory but includes an democratic empirical component is the consensual method pioneered by Mack & Lansley (1985). The consensual deprivation approach was a ground-breaking approach in that it linked the theory of relative deprivation with an actual account of the socially perceived needs of the population. More recently, from the capability perspective, other studies have also aimed at finding the necessities of life by asking the population (Clark & Qizilbash, 2005; Narayan, 2001).

Although the specification via theory and/or some form of empirical data helps to delimit the space of relevant needs, it does not solve problems about the interaction between indicators and dimensions. More importantly, it does not guarantee that such a list would effectively result in an accurate account of the dimensions of poverty. There are several reasons. One criticism is reflected in the argument pose by McKay (2004) about the difference between needs and preferences (i.e. How to split between wishes from constraint?). Another critique is about on what basis one decides what is a need from what is not when there is no 100% endorsement (Bradshaw, Holmes, & Hallerod, 1995). Another argument has been about the difficulties to conduct comparative work, i.e. how to compare countries with different sets of needs. There is, from statistical point of view -which is the topic of this book-, a satisfactory response to these concerns. We will recover these critiques throughout the book as a key task of it is to provide a profound explanation and illustration of why once some principles of measurement theory are fulfilled, these critiques do not hold.

The determination of thresholds levels for the indicators and dimensions is central as it is one of the main sources of variability of an index. Thorbecke (2007) points out that this is often done on a subjective or normative fashion and that it could lead to important discrepancies and reproducibility problems. Aside theory-driven ways to set the thresholds of nominal variables, the consensual approach could be also used to find a split. The best example is the Mexican Multidimensional Measure in that the cut offs where derived from the consensual method and a revision of the norms in Mexico CONEVAL (2011a) (Chapter XX shows how this hybrid approach leads to a more robust measure). Rightly so, Thorbecke (2007) indicates that the key is to find a series of cut offs that yield to a consistent ranking of the population given the observed outcome measures of deprivation.

1.3.2 Challenges in aggregation and identification of the poor

Finding the spaces of needs, dimensions and cut offs is just one stage in poverty measurement. (Thorbecke, 2007, p. 7) makes the following point:

Now let us assume that, notwithstanding all the difficulties discussed above, agreement has been reached on a list of attributes related to poverty and their threshold levels. How can such information be used to derive measures of multidimensional poverty and make poverty comparisons? Start with the simplest case, for example, that of an individual who is below each and every attribute threshold level. Such a person would be classified as unambiguously poor. Analogously, comparing two individual poverty profiles (A and B) where the attribute scores for all of the n dimensions in the profile of A are above that of the profile of B, it can be inferred unambiguously that A is better off in terms of well-being (less poor) than B.

The question about how to aggregate the indicators and then how to split the population into two meaningful groups (i.e. poor and not poor) has been present since the classic studies of poverty. From a theoretical perspective there have been three responses to this question. Townsend (1979) put forward a theory that stated that there must be a level of resources (the cause) from which deprivation raises substantially (consequence) (This is also known as the Townsend breaking point). Such a point should be the poverty line in that it leads to a meaningful split of the population, i.e. people whose standard of living is so low that they are effectively excluded from the patterns of living in society. Within this approach the aggregation consists in counting the number of deprivations and finding an optimal split based on its relationship with resources. P. Townsend & Gordon (1993) argue that when using cross-sectional data, the best approach is the intersection -below certain level of resources and above certain level of deprivation- (See (Gordon, 2010)). This is the approach, for example, adopted to identify the poor in Mexico (CONEVAL, 2011a). One distinctive aspect of the Townsend breaking point is that the dimensions do not figure although the accounting of the diversity of attributes of deprivation remains.

A second theory-driven approach consists in using the union approach (being deprived in either resources or basic needs). This approach is used as part of Boltvinik’s integrated method (Boltvinik & Hernández-Láos, 2001). The IMMP aims to minimize the exclusion of the poor and the view that income, deprivation of needs and time deprivation are three attributes to characterise poverty. This is different from (Townsend, 1979)’s theory where needs deprivation is a manifestation of low command of resources (See (Gordon, 2010, p. @Cortes2014) for a discussion from the perspective of poverty dynamics and human rights).

Unlike the first two approaches, the third main approach focuses more on the aggregation of the indicators than on how to set the poverty line (Foster, Greer, & Thorbecke, 2010). The axiomatic approach was pioneered by Sen (1976) for income-based measures. Sen (1976) put emphasis on the importance of the aggregation stage in poverty measure as it had consequences for the decomposition and analysis beyond the prevalence of poverty. Two axioms were critical for Sen (1976): monotonicity (poverty rise if income falls) and transfer (poverty rise if there is a transfer from the poor to the rich). Later Foster, Greer, & Thorbecke (1984) extended Sen’s axioms and this formulation has been developed for multidimensional measures (Tsui, 2002, pp. Alkire2011a, Alkire2015).

The AF index respect several desirable axioms such as monotonicity and other axioms such as symmetry, replication invariance, scale invariance, poverty focus and population subgroup decomposability (Alkire et al., 2015, see for a complete description). It results in an aggregation method that produces and index with properties that are true without proof.

\[ P_{AF}(X;z)= \frac{1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\sum _{j=1}^{d}w_{j}g^{\alpha }_{jk}(k);\alpha\geq0 \]

In their formulation \(x\) are achievements in the form of indicators or dimensions from a matrix \(X\) and \(z\) and the cut-offs for identifying the poor \(x_{ij}<z_j\), \(i\), are individuals or households and \(j\) the dimensions. A person is deprived in the dimension (\(g^{0}_{ij}=1\)). Weights are included via \(w_j\), and \(\alpha=0\) is the adjusted headcount ratio and \(\alpha=1\) the adjusted poverty gap.

One crucial aspect that is often and wrongly overlooked when considering the axiomatic approach is the difference between an aggregation method (formula) and a measurement methodology (series of steps). The Alikre-Foster (AF) family of measures impose a series of axioms so that the behaviour of a formula is predictable. The fact that is based on axioms does not make the measurement of poverty based on the AF method true or correct. The axiomatic approach, as any other measure, is based on the key assumption that the indicators (cut offs), weights and dimensions are a sensible account of poverty. Unlike the aggregation used in the counting approach, this aggregation method, explicitly takes into account relative welfare weights (S. Alkire & Foster, 2011). The issue of weighting will be discussed in detail in Chapter 3 but as in the previous case, measurement theory offers a framework to deal with this issue under a falsifiable framework. One of the aims of this book is to clarify why the principles of measurement theory are a necessary condition for the AF to work, whereas the AF is not so for an index that fulfils the core principles of measurement theory.

1.4 The poor and the not poor: The poverty line

From a conceptual basis, the poverty line could be defined as the minimum living standards acceptable in a society at a given point in time. The poverty line is often expressed in either monetary or non-monetary terms (i.e. deprivation weighted count). This is not a book on income poverty measurement but when using an indirect approach Van den Bosch (2001) identifies the following methods.2 Peter Townsend (1993) discusses the problems with this type of approach:

- Budget standards: The price of a specific basket of goods and services. This approach was used by Rowntree (1901) and recently most notably by Bradshaw (1993) and Bradshaw et al. (2008).

- Official standards: An arbitrary price or deprivation count is used by an statistical agency to split the population. It is often based on the minimum income support offered by the social security system.

- Food-ratio method: It assumes that living standards can be judge by comparing the proportion of income spend on necessities.

- Relative method: The income threshold is set to a certain percentage of the mean or median income. Some European countries use 60% of the median income, for example.

The introduction of direct approaches to capture poverty has opened up a discussion about whether income and deprivation should be combined to identify the poor (Boltvinik, 1998, 2014; Boltvinik & Hernández-Láos, 2001; Gordon, 2010). In the literature, this is known as the debate between union and intersection approaches. The union approach sees income and deprivation as two measures of the same phenomenon and therefore being below of a certain cut off in either of the two leads to poverty. In contrast, the intersection approach acknowledges that these should be used jointly to identify the poor, i.e. lacking both sufficient income and being multiply deprived is poverty. For Boltvinik & Hernández-Láos (2001) the union minimizes the exclusion of the poor and the intersection maximizes its exclusion. So the first one overestimates poverty and the second is an underestimate. A third option is a partial union approach (S. Alkire & Roche, 2011; Santos & Villatoro, 2016). Income is first dichotomized using \((x;z)\) a cut off. Then, income is included in a score as another deprivation in the AF aggregation method. The partial inclusion is obtained by using differential weights and by setting a poverty line based on a percentage of the total possible deprivation score (Typically 25%).

One practical argument in favour of the intersection approach is given from the perspective of poverty dynamics. When using cross-sectional data is not possible to assess the individual trend in deprivation followed a rise or fall of resources. That is, some households having just experienced a rise in income are expected to be less deprived in the incoming future. However, the snapshot of the cross-sectional survey would put them as poor under the union approach when in reality they are at risk or vulnerable to poverty (Katzman, 2000). Only with high-quality panel data would be possible to identify the truly poor based on the union approach (Gordon, 2006; Halleröd, 1995).

When discussing poverty lines is important to ask what the underlying theory behind the different approaches is? Unfortunately, theories are rarely explicit and imprecise with regard the poverty line. There are three main approaches to set the poverty line:

- Townsend’s breaking point: One explicit framework is given by Townsend (1979) and Peter Townsend (1993). One of the predictions of Townsend’s theory is that there is a negative relationship between resources and deprivation. Yet, he proposed that such relationship is not linear, and that multiple deprivation raises considerably below a certain level of resources.

- Normative approach based on social rights: Social rights are indivisible and interrelated so being deprived of one right captures a situation of denial of basic human needs. CONEVAL (2011a) uses 1+ deprivation and an income below an income poverty line (drawn from a budget standards approach) to identify the poor (Cortés, 2014).

- Normative approach integrated method: Boltvinik & Hernández-Láos (2001) proposes that poverty has three dimensions: time, resources and UBN. People is regarded as poor when failing to meet one of the three dimensions.

- Arbitrary approach: Without any theoretical justification, some researchers set the poverty at some value below 50% of the total weighted sum of deprivations. For example, if there are 10 deprivation and the cut off is 30%, people with three or more deprivations are regarded as poor.

These theoretical and methodological discrepancies lead to considerably differences in the extent of poverty. This is true even when the same indicators are utilized for two measures with different strategies to set the poverty line. This begs the question about how to tackle this challenge from an empirical perspective. This topic is covered in the next chapter of the book.

1.5 A brief on multidimensional poverty measurement

The debates about the definition of poverty and the best way to measure it have, of course, been reflected in different approaches to capture this phenomenon. The diverse views about how to produce a poverty scale have shaped the history and types of poverty measures. Poverty research and measurement has more than 100 years of history. The ground-breaking and now classic studies of Rowntree (1901) Poverty: A study of Town Life', @Booth1903'sLife and Labour of the People in London’ and Townsend (1979)‘s `Poverty in the UK’ were possible after years of relentless research that aimed to understand the extent, distribution and nature of poverty. A common feature across these studies is that all used an ex ante developed questionnaire to capture poverty. This is in stark contrast with current practices in poverty research as poverty is seldom measured using explicitly developed questionnaires. There are important differences among these three monumental studies. Perhaps the most fundamental is that Townsend (1979)’s study was fully theory driven and used direct indicators of poverty (deprivation) and not income.

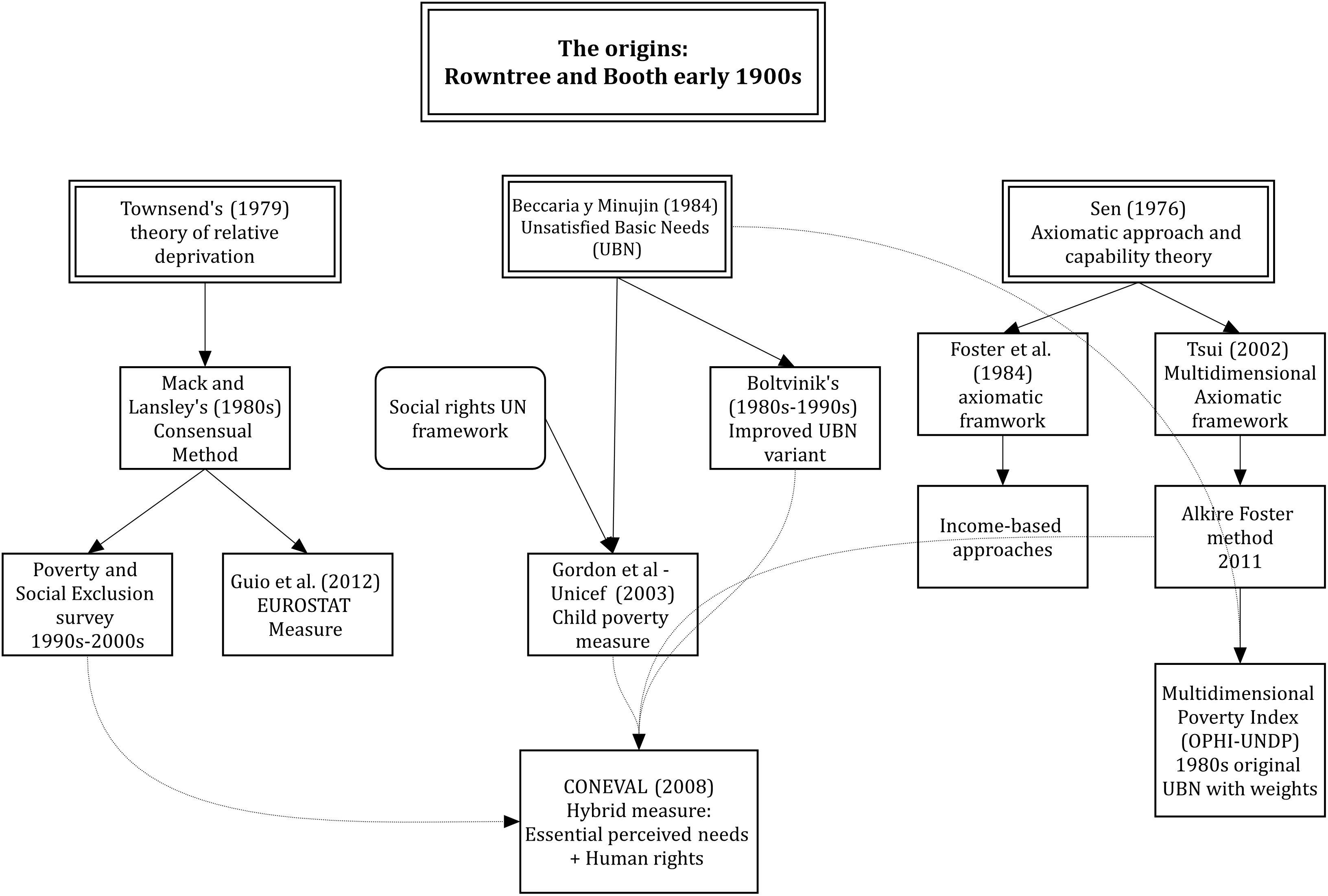

The legacy of these studies has been such that the poverty research agenda dramatically expanded in the late XX and early XXI Centuries. Figure 1.1 synthetizes rather crudely the recent history of multidimensional poverty measurement. The multidimensional approach to poverty has its roots in both Europe and Latin America in 1960s and 1970s. Latin America was at the forefront in multidimensional poverty measurement thanks to the Unsatisfied Basic Needs (UBN) approach which used direct indicators to capture poverty [Altimir (1979);Beccaria1985;Boltvinik1992;Boltvinik2001]. The indicators have been mainly focused on housing and essential services given that the implementation of the UBN has been constrained by the available data. Boltvinik & Hernández-Láos (2001) adjusted variant of the UBN approach is perhaps the most theoretically comprehensive and progressive in that includes time as a dimension. The UBN has become a widely known tradition in poverty measurement and has shaped contemporary measures such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNPD) multidimensional poverty index (MPI) and has greatly influenced official measures such as the Mexican measure (CONEVAL, 2011b).

In the developed world, Townsend (1979)’s theory of deprivation not only served to produce the first survey questionnaire to measure multidimensional poverty but also proposed a direct and multidimensional measure of poverty. In the 1980s, the use of direct indicators to measure poverty was further suggested during the series of exchanges between Townsend (1985) and Sen (1983) and Sen (1985). This despite the focus of their argument was relative versus absolute poverty. This is not a book on monetary poverty, but Sen’s axiomatic framework set the bases for the development of axioms for multidimensional measures Sen (1976) and Foster et al. (1984).

In the late 1980s and 1990s Townsend’s influence on poverty measurement was boosted by Mack & Lansley (1985)’s consensual approach that added the exploration of needs as a vital component to relative deprivation theory. Europe continued with the relative deprivation tradition but other parts of the world introduced monetary measurement of poverty (including Latin America), which became the mainstream approach in developing countries and led to the World Bank approach and the inevitable and rich debate about it (Pogge, 2005; Ravallion, 2010; Reddy & Pogge, 2010).

Figure 1.1: A brief summary of the history of poverty measurement

The XXI Century was witnessed the resurgence of multidimensional measurement. In Europe the Poverty and Social Exclusion series has continued Townsend’s tradition in the UK Townsend & Gordon (2000), Pantazis, Gordon, & Levitas (2006) and Mack & Lansley (1985) have had a major influence in the measurement of poverty in Europe (Atkinson, Guio, & Marlier, 2017; Whelan et al., 2006). In economics, the axiomatic approach has been extended for multidimensional measures (Foster et al., 2010; Tsui, 2002). These contributions and the capability theory as overarching framework have been very influential in multidimensional poverty measurement (S. Alkire & Foster, 2011; Alkire et al., 2015; Kakwani & Silber, 2008). Although as Boltvinik (2014) points out, the axiomatic approach depends more on the UBN than the UBN on the axiomatic and capability approach. Making unclear what is the actual innovation of the multidimensional axiomatic approach.

Similarly, the emergence of the human rights approach in the early 2000s in poverty measurement has been closely tied with the UBN approach. Nonetheless, the efforts to articulate human rights and multidimensional poverty measurement have helped to the progressive institutionalisation either by nations or by international institutions of official multidimensional measures (Boltvinik, 2014; CONEVAL, 2011a). The work Gordon et al. (2003) on child poverty pioneered the era of global harmonized multidimensional poverty measurement by drawing upon human rights and UBN. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) global acute poverty measure in collaboration with the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) that recovers some key dimensions of the UBN approach and aggregates the indicators using the AF methodology (Alkire & Santos, 2010; UNDP, 2014). The most recent regional example is the EUROSTAT deprivation index that draws on relative deprivation and the consensual method (Guio et al., 2017, 2016).

Only two official measure have been put to statistical scrutiny: EUROSTAT and CONEVAL. The EUROSTAT measure was produced by Guio et al. (2012) and revalidated by Guio et al. (2017). It is based on the consensual approach and relative deprivation theory and has been fully statistically validated. The reason why there are several arrows pointing at the CONEVAL measure (the official Mexican measure) is that this is arguably the first official multidimensional measure and it had a desirable process for its production. After a critical change of the Social Development Law in 2004, Mexico was obliged to measure poverty from a multidimensional perspective and in accordance with the constitution. This resulted in an international consultation process. Mora (2010) compiled the different contributions of the authors and CONEVAL (2011b) summarises the contributions of each author. The resulting measure is a hybrid measure that benefit from an international collaboration and it has been the first one to be fully statistically validated before its production. Townsend (1979) and the consensual approach were used to assess the thresholds for the nominal variables and provide a view on the socially perceived needs of the Mexican population with focus on social rights. Then Gordon (2010) conducted a preliminary evaluation of the indicators of the measure and suggested an approach to identify the poor and the not poor. Then the AF method was used to estimate the depth and intensity measures for income and the deprivation score.

Both EUROSTAT and CONEVAL have succeeded in producing measures that are not only theoretically sound but are also empirically validated. This is, nonetheless, an exception to the current practices in poverty research. However, more recent initiatives such as the Atkinson report, the call of UNDP to validate some aspects of the global OPHI-MPI, and some practices in academic journals are pushing toward making statistical scrutiny a standard practice in multidimensional poverty measurement, as it happens in other fields. The remainder of the book thus focuses on a proposal that aims to avoid producing magnifying-noise scales.

The notation is fully introduced in the following sections but will introduce it also little by little to help not mathematical readers: specific outcomes/deprivation/achievements \(\mathbf{x}\) and the full set of outcomes \(\mathbf{X}\))↩

The calorie-based income poverty line is another popular method, which is based on the presumption that the poor cannot meet their energy requirements -based on a reference basket-↩